Henry Walter Bates (Leicester, 8 de fevereiro de 1825 — Londres, 16 de fevereiro de 1892) foi um entomólogo e naturalista inglês.

Famoso por sua viagem à Amazônia, junto com Alfred Russel Wallace, com o objetivo de recolher material zoológico e botânico para o Museu de História Natural de Londres.

Permaneceu no Brasil durante onze anos, enviando cerca de 14.712 espécies (8000 delas novas), a maior parte insetos para a Inglaterra. Após o seu trabalho nas florestas tropicais do Brasil, propôs o mecanismo de Mimetismo batesiano, uma uma forma de mimetismo em que uma espécie

evolui características morfológicas ou outras que a fazem aparentar com

outra espécie considerada repugnante pelo predador, concedendo-lhe uma

certa protecção contra predação. Em 1861 casou com Sarah Ann Mason e a partir de 1864 trabalhou como secretário assistente da Royal Geographical Society. Foi acompanhado de seu sócio e amigo Alfred

Russel Wallace, juntos excursionaram pelo rio Tocantins, em busca de dados sobre a origem

das espécies (1848-1852), catalogou cerca de 8000 insetos

até então desconhecidos numa coletânea de 14.712 espécies

da fauna da América do Sul, que muito contribuiu para o progresso

dos estudos zoológicos. Na sua volta à Inglaterra

(1859) apresentou à Linnean Society a monografia Contributions

to an Insect Fauna of the Amazon Valley (1861), que mereceu o aplauso

de Charles Darwin, que utilizou muitos dos dados para elaborar sua

teoria sobre a origem das espécies. Nomeado secretário-assistente

da Royal Geographical Society (1864), foi eleito para a Royal Society (1881)

e morreu em Londres de bronquite. Publicou na Inglaterra vários livros sobre

a Amazônia sendo o mais conhecido The Naturalist on The River

Amazons (1863), traduzido no Brasil como O naturalista no Rio Amazonas

(1944) na sua primeira edição, com tradução de Candido de Mello Leitão, e posteriormente, como Um naturalista no Rio Amazonas (1979) com tradução de Regina Régis Junqueira.

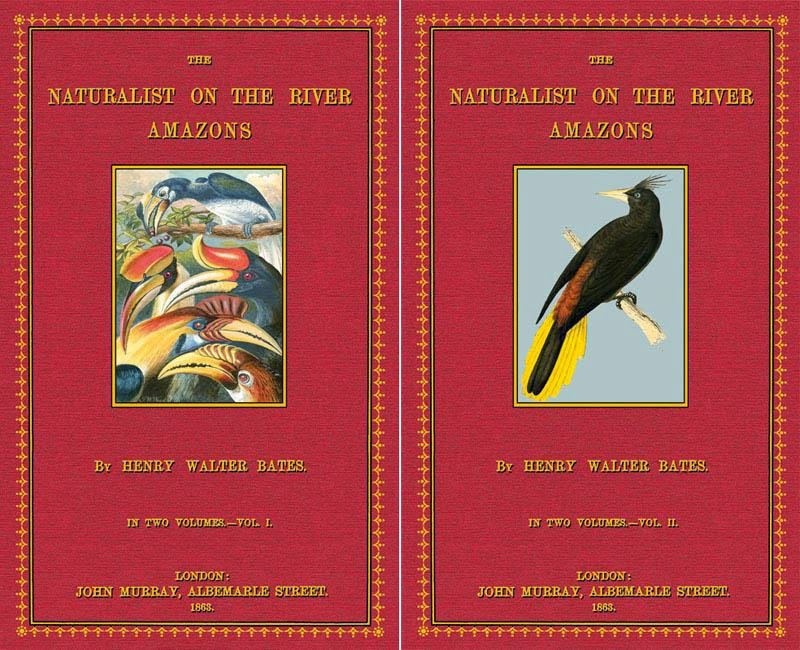

Edições do - The naturalist on the River Amazons

1 Edição. 1863. 2 v

Bates, H.W. 1863. THE NATURALIST ON THE RIVER AMAZONS, A RECORD OF

ADVENTURES, HABITS OF ANIMALS, SKETCHES OF BRAZILIAN AND INDIAN LIFE,

AND ASPECTS OF NATURE UNDER THE EQUATOR, DURING ELEVEN YEARS OF TRAVEL.

LONDON: JOHN MURRAY, 2 volumes, 8vo, (vol.1) viii, [ii],

352pp., 32 pp. adverts dated January 1863; (vol.2) vi, 424 pp., folding

map, 9 wood-engraved plates, illustrations

__________________________________________________________________

2 Edição. 1864. 1 v.

|

| Adicionar legenda |

Bates H.W. 1864. The naturalist on the river Amazons. 2nd. London, John Murray, 1864, First one-volume

edition, published the year after the first edition in two volumes.,

8vo [20.5 x 13.5 cm]; xii, 466, [ii, ads] pp, frontis, numerous

plates and illustrations, foldout map of the Amazons from its mouth to

Peru, with two map insets, index. original green pictorial gilt cloth,

gilt spine title lettering, owner's signature on endpaper, internal

hinge cracked but firm, edges lightly rubbed, but a very good copy, gilt

bright. Borba de Moraes p 91 for 1st edition. The rare first edition of

this classic of natural history exploration was published in London

1863. This second edition omits some of the technical detail but

includes the entire personal narrative and most description of the

natural history. The folding map which is present was not included in

later editions. Bates, who spent over 11 years in the Amazon area,

formed an enormous collection of 14,000 insects, which occupied

scientists for years in classifying them. He went to South America with

Alfred Russell Wallace and the two journeyed together for a time. Darwin

encouraged him to write the book and recommended it for publication. In

Darwin's words: "Bates is only excelled by Humboldt in his description

of the tropical forest". His observations contributed to the theory of

evolution, hence the importance of this book. "A splendid travel book"

(Knight p. 180). Welch 33. Humphreys 1447. Goodman 606: 'One of the most

interesting and pleasing of all the works written by the explorers.'

The Dictionary of Scientific Biography describes it as 'one of the

finest scientific travel books of the 19th century'. This truncated edition which is

usually reprinted. Advice: use the 1863 or 1892 editions for

professional purposes] (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 978-1-108-00163-2)

__________________________________________

3 Edição. 1892. 1 v.

Bates H.W. 1892. The naturalist on the river Amazons, with a memoir of the author by Edward Clodd.

[this edition, published after Bates' death, is valuable for two

reasons: it is the only time since 1863 that Murray published the full

text, and it includes a good short biography by Clodd]. Reprint of the Unabridged 2 Edition. 240mm x 160mm (9" x 6").

395pp. Map and Numerous illustrations, including colour plates.

Outras Edições em Inglês

_______________________________________

EDIÇÃO EM ALEMÃO

Elf Jahre am Amazonas

Edições de Henry Bates no Brasil - - O naturalista no Rio Amazonas / Um naturalista no Rio Amazonas

1 Edição no Brasil

BATES, Henry Walter.O naturalista do rio Amazonas. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional, 1944. 1 ed. 2 v. (Brasiliana, 237). 2 Vlos.

Série 5ª brasiliana vol 237

Tradução Candido de Mello Leitão.

376 + 398 Pags. 18, 5 cms.

Este volume é disponível em: O naturalista no rio Amazonas - Henry W. Bates

_______________________________________________

2 Edição no Brasil

BATES, Henry Walter. Um naturalista do rio Amazonas. Belo Horizonte : Ed. Itatia. São Paulo: Ed. da Universidade de Sao Paulo. 1979. 2 ed. 2 v. (Reconquista do Brasil, v. 53). Tradução Regina Régis Junqueira

História do período de estadia de Henry Bates no Brasil

Fonte:http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Bates,_Henry_Walter_%28DNB01%29

In the meantime, however, he had made the acquaintance of Mr. Alfred

Russel Wallace, then English master at the collegiate school,

Leicester. The works of Humboldt and Lyell, and Darwin's recently

published 'Journal' (1839), proved a bond of communion between them.

They were both also enthusiastic entomologists, and were alike growing

dissatisfied with their restricted collecting area. The friends began to

discuss schemes for going abroad to explore some unharvested region,

and these at length took definite shape, mainly owing to the interest

excited by a little book by William H. Edwards on 'A Voyage up the River

Amazon, including a residence at Pará' (New York, 1847). This led Mr.

Wallace to propose to Bates a joint expedition to the Amazons, the plan

being to collect largely and dispose of duplicates in London in order to

defray expenses, while gathering facts towards solving the problem of

the origin of species. They embarked at Liverpool in a small trading

vessel of 192 tons on 26 April 1848, and arrived off Pará on 27 May.

Bates made Pará his headquarters until 6 Nov. 1851, when he started on

his long voyage to the Tapajos and the Upper Amazons, which occupied a

period of seven years and a half. It was from Pará that he and Mr.

Wallace in August 1848 made an excursion up the river Tocantins, the

third in rank among the streams which make up the Amazons system, of the

grandeur and peculiarities of which he wrote a striking account. In

September 1849 he started on his first voyage up the main stream in a

small sailing vessel (a service of steamers was not established until

1853), and reached Santarem, which he subsequently made his headquarters

for a period of three years; but on this journey he pushed on to

Obydos, about fifty miles further on. Here he secured a passage in a

cuberta or small vessel proceeding with merchandise up the Rio Negro.

The destination of the boat was Manaos on the Barra of the Rio Negro, a

spot rendered memorable by the visit of the Dutch naturalists, Spix and

Martins, in 1820. Here, some thousand miles from Pará, in March 1850

Bates and Wallace parted company, 'finding it more convenient to explore

separate districts and collect independently.' Wallace took the

northern parts and tributaries of the Amazons, and Bates kept to the

main stream, which, from the direction it seems to take at the fork of

the Rio Negro, is called the Upper Amazons, or the Solimoens. After

sailing three hundred and seventy miles up the Solimoens, through 'one

uniform, lofty, impervious, and humid forest,' Bates arrived on May-day

1850 at Ega. Here he spent nearly twelve months before returning to

Pará, and thus finished what may be considered as his preliminary survey

of the vast collecting ground which will always be associated with his

name. In November 1851 he again arrived at Santarem, where, after a

residence of six months, he commenced arrangements for an excursion up

the little-known Tapajos river, which in magnitude stands sixth among

the tributaries of the Amazons. A stay was made at the small settlement

of Aveyros, and from this spot an expedition was made up the Cupari, a

branch river which enters the Tapajos about eight miles above it. At

this time he was thrown into contact with Mundurucii Indians, and was

able to acquire much valuable ethnological information. The furthest

point up the Amazons system that he visited (in Sept. 1857) was St.

Paulo, a few leagues north east of Tabatinga and the Peruvian frontier.

From June 1864 until February 1859 Bates made his head-quarters 1,400

miles above Pará, at Ega, a place which he made familiar by name to

every European naturalist as the home of entomological discoveries of

the highest interest. At Ega he found five hundred and fifty new and

distinct species of butterflies alone (the outside total of English

species being no more than sixty-six). On the wings of these insects he

wrote in a memorable passage, 'Nature writes as on a tablet the story of

the modifications of species.' During the whole of his sojourn amid the

Brazilian forests his speculations were approximating to the theory of

natural selection, and upon the publication of the 'Origin of Species'

(November 1859) he became a staunch and thoroughgoing adherent of the

Darwinian hypothesis.

On 11 Feb. 1859 Bates left Ega for England, having spent eleven of

the best years of his life within four degrees of the equator, among

many discouragements, and to the detriment of his health, but to the

permanent enrichment of our knowledge of one of the most interesting

regions of the globe. During his stay in the Amazons he had learned

German and Portuguese, had discovered over eight thousand species new to

science, and by the sale of specimens had made a profit of about 800l.

He sailed from Pará on 2 June 1859, and upon his arrival set to work at

once upon his collections. His philosophic insight was first fully

exhibited in his celebrated paper, read before the Linnean Society on 21

June 1861, 'Contri- butions to an Insect Fauna of the Amazon Valley. Lepidoptera : KeViconidæ' (Linnean Soc. Trans,

vol. xxiii. 1862), described by Darwin as 'one of the most remarkable

and admirable papers I ever read in my life.' It was this paper which

first gave a due prominence before the scientific world to the

phenomenon of mimicry, and with it a philosophic explanation which at

once received Darwin's unconditional acceptance. 'I rejoice,' wrote the

latter with characteristic sincerity, 'that I passed over the whole

subject in the "Origin," for I should have made a precious mess of it '

(cf. Poulton, Colours of Aniynals,

pp. 217 sq. ; Beddaed, Animal Coloration, passim ; Grant Allen on

'Mimicry,' Encyel. Brit. 9th ed.) Darwin strongly recommended Bates to

publish a narrative of his travels, and with this object introduced him

to the publisher, John Murray, who proved an invaluable friend. In

January 1863 Murray issued Bates's 'Naturalist on the Amazons', which

has been described as 'the best work of natural history travels

published in England.' Apart from the personal charm of the narrative.

Bates as a describer of the tropical forest is second only to Humboldt.

His breadth of view saved him from the narrowness of specialism, and he

was as far removed as possible from what Darwin called 'the mob of

naturalists without souls.' The book was highly praised in the 'Revue

des Deux Mondes' for August 1863, but the highest compliment it received

was the remark of John Gould (whose greatest ambition had been to see

the great river) to the author : 'Bates, I have read your book — I've

seen the Amazons.' In April 1862, by the advice of numerous friends.

Bates applied for a post in the zoological department at the British

Museum, but the post was given to the poet Arthur William Edgar

0'Shaughnessy [q.v.], whose mind was a tabula rasa as far as zoological knowledge was concerned.

___________________________

Revisão Critica de Charles Darwin

Author of "The Origin of Species," etc.

[From Natural History Review, vol. iii. 1863.]

IN April, 1848, the author of the present volume left

England in company with Mr. A. R. Wallace--"who has since acquired wide

fame in connection with the Darwinian theory of Natural Selection"--on a

joint expedition up the river Amazons, for the purpose of investigating the

Natural History of the vast wood-region traversed by that mighty river and its

numerous tributaries. Mr. Wallace returned to England after four years' stay,

and was, we believe, unlucky enough to lose the greater part of his collections

by the shipwreck of the vessel in which he had transmitted them to London. Mr.

Bates prolonged his residence in the Amazon valley seven years after Mr.

Wallace's departure, and did not revisit his native country again until 1859.

Mr. Bates was also more fortunate than his companion in bringing his gathered

treasures home to England in safety. So great, indeed, was the mass of

specimens accumulated by Mr. Bates during his eleven years' researches, that

upon the working out of his collection, which has been accomplished (or is now

in course of being accomplished) by different scientific naturalists in this

country, it has been ascertained that representatives of no less than 14,712

species are amongst them, of which about 8000 were previously unknown to science.

It may be remarked that by far the greater portion of these species, namely,

about 14,000, belong to the class of Insects--to the study of which Mr. Bates

principally devoted his attention--being, as is well known, himself recognised

as no mean authority as regards this class of organic beings. In his present

volume, however, Mr. Bates does not confine himself to his entomological

discoveries, nor to any other branch of Natural History, but supplies a general

outline of his adventures during his journeyings up and down the mighty river,

and a variety of information concerning every object of interest, whether

physical or political, that he met with by the way. Mr. Bates landed at Para in

May, 1848. His first part is entirely taken up with an account of the Lower

Amazons--that is, the river from its sources up to the city of Manaos or Barra

do Rio Negro, where it is joined by the large northern confluent of that name--

and with a narrative of his residence at Para and his various excursions in the

neighbourhood of that city. The large collection made by Mr. Bates of the

animal productions of Para enabled him to arrive at the following conclusions

regarding the relations of the Fauna of the south side of the Amazonian delta

with those of other regions. "It is generally allowed that Guiana and

Brazil, to the north and south of the Para district, form two distinct

provinces, as regards their animal and vegetable inhabitants. By this it means

that the two regions have a very large number of forms peculiar to themselves,

and which are supposed not to have been derived from other quarters during

modern geological times. Each may be considered as a centre of distribution in

the latest process of dissemination of species over the surface of tropical

America. Para lies midway between the two centres, each of which has a nucleus

of elevated table-land, whilst the intermediate river- valley forms a wide

extent of low-lying country. It is, therefore, interesting to ascertain from

which the latter received its population, or whether it contains so large a

number of endemic species as would warrant the conclusion that it is itself an

independent province. To assist in deciding such questions as these, we must

compare closely the species found in the district with those of the other

contiguous regions, and endeavour to ascertain whether they are identical, or

only slightly modified, or whether they are highly peculiar. "Von Martius

when he visited this part of Brazil forty years ago, coming from the south, was

much struck with the dissimilarity of the animal and vegetable productions to

those of other parts of Brazil. In fact the Fauna of Para, and the lower part

of the Amazons has no close relationship with that of Brazil proper; but it has

a very great affinity with that of the coast region of Guiana, from Cayenne to

Demerara. If we may judge from the results afforded by the study of certain

families of insects, no peculiar Brazilian forms are found in the Para

district; whilst more than one-half of the total number are essentially Guiana

species, being found nowhere else but in Guiana and Amazonia. Many of them,

however, are modified from the Guiana type, and about one-seventh seem to be

restricted to Para. These endemic species are not highly peculiar, and they may

yet be found over a great part of Northern Brazil when the country is better

explored. They do not warrant us in concluding that the district forms an

independent province, although they show that its Fauna is not wholly

derivative, and that the land is probably not entirely a new formation. From

all these facts, I think we must conclude that the Para district belongs to the

Guiana province and that, if it is newer land than Guiana, it must have

received the great bulk of its animal population from that region. I am informed

by Dr. Sclater that similar results are derivable from the comparison of the

birds of these countries." One of the most interesting excursions made by

Mr. Bates from Para was the ascent of the river Tocantins--the mouth of which

lies about 4-5 miles from the city of Para. This was twice attempted. On the

second occasion--our author being in company with Mr. Wallace--the travellers

penetrated as far as the rapids of Arroyos, about 130 miles from its mouth.

This district is one of the chief collecting-grounds of the well-known

Brazil-nut (Bertholletia excelsa), which is here very plentiful, grove after

grove of these splendid trees being visible, towering above their fellows, with

the "woody fruits, large and round as cannon-balls, dotted over the branches."

The Hyacinthine Macaw (Ara hyacinthina) is another natural wonder, first met

with here. This splendid bird, which is occasionally brought alive to the

Zoological Gardens of Europe, "only occurs in the interior of Brazil, from

16' S.L. to the southern border of the Amazon valley." Its enormous

beak--which must strike even the most unobservant with wonder--appears to be

adapted to enable it to feed on the nuts of the Mucuja Palm (Acrocomia

lasiospatha). "These nuts, which are so hard as to be difficult to break

with a heavy hammer, are crushed to a pulp by the powerful beak of this

Macaw." Mr. Bates' later part is mainly devoted to his residence at

Santarem, at the junction of the Rio Tapajos with the main stream, and to his

account of Upper Amazon, or Solimoens--the Fauna of which is, as we shall

presently see, in many respects very different from that of the lower part of

the river. At Santarem--"the most important and most civilised settlement

on the Amazon, between the Atlantic and Para "--Mr. Bates made his

headquarters for three years and a half, during which time several excursions

up the little-known Tapajos were effected. Some 70 miles up the stream, on its

affluent, the Cupari, a new Fauna, for the most part very distinct from that of

the lower part of the same stream, was entered upon. "At the same time a

considerable proportion of the Cupari species were identical with those of Ega,

on the Upper Amazon, a district eight times further removed than the village

just mentioned." Mr. Bates was more successful here than on his excursion

up the Tocantins, and obtained twenty new species of fishes, and many new and

conspicuous insects, apparently peculiar to this part of the Amazonian valley.

In a later chapter Mr. Bates commences his account of the Solimoens, or Upper

Amazons, on the banks of which he passed four years and a half. The country is

a "magnificent wilderness, where civilised man has, as yet, scarcely

obtained a footing-the cultivated ground, from the Rio Negro to the Andes,

amounting only to a few score acres." During the whole of this time Mr.

Bates' headquarters were at Ega, on the Teffe, a confluent of the great river

from the south, whence excursions were made sometimes for 300 or 400 miles into

the interior. In the intervals Mr. Bates followed his pursuit as a collecting

naturalist in the same "peaceful, regular way," as he might have done

in a European village. Our author draws a most striking picture of the quiet,

secluded life he led in this far-distant spot. The difficulty of getting news

and the want of intellectual society were the great drawbacks--"the latter

increasing until it became almost insupportable." "I was obliged at

last," Mr. Bates naively remarks, "to come to the conclusion that the

contemplation of Nature, alone is not sufficient to fill the human heart and

mind." Mr. Bates must indeed have been driven to great straits as regards

his mental food, when, as he tell us, he took to reading the Athenaeum three

times over, "the first time devouring the more interesting articles--the

second, the whole of the remainder--and the third, reading all the

advertisements from beginning to end." Ega was, indeed, as Mr. Bates

remarks, a fine field for a Natural History collector, the only previous

scientific visitants to that region having been the German Naturalists, Spix

and Martius, and the Count de Castelnau when he descended the Amazons from the

Pacific. Mr. Bates' account of the monkeys of the genera Brachyuyus,

Nyctipithecus and Midas met with in this region, and the whole of the very

pregnant remarks which follow on the American forms of the Quadrumana, will be

read with interest by every one, particularly by those who pay attention to the

important subject of geographical distribution. We need hardly say that Mr.

Bates, after the attention he has bestowed upon this question, is a zealous

advocate of the hypothesis of the origin of species by derivation from a common

stock. After giving an outline of the general distribution of Monkeys, he

clearly argues that unless the "common origin at least of the species of a

family be admitted, the problem of their distribution must remain an

inexplicable mystery." Mr. Bates evidently thoroughly understands the

nature of this interesting problem, and in another passage, in which the very

singular distribution of the Butterflies of the genus Heliconius is enlarged

upon, concludes with the following significant remarks upon this important

subject: "In the controversy which is being waged amongst Naturalists

since the publication of the Darwinian theory of the origin of species, it has

been rightly said that no proof at present existed of the production of a

physiological species, that is, a form which will not interbreed with the one

from which it was derived, although given ample opportunities of doing so, and

does not exhibit signs of reverting to its parent form when placed under the

same conditions with it. Morphological species, that is, forms which differ to

an amount that would justify their being considered good species, have been

produced in plenty through selection by man out of variations arising under

domestication or cultivation. The facts just given are therefore of some

scientific importance, for they tend to show that a physiological species can

be and is produced in nature out of the varieties of a pre-existing closely

allied one. This is not an isolated case, for I observed in the course of my

travels a number of similar instances. But in very few has it happened that the

species which clearly appears to be the parent, co-exists with one that has

been evidently derived from it. Generally the supposed parent also seems to

have been modified, and then the demonstration is not so clear, for some of the

links in the chain of variation are wanting. The process of origination of a

species in nature as it takes place successively, must be ever, perhaps, beyond

man's power to trace, on account of the great lapse of time it requires. But we

can obtain a fair view of it by tracing a variable and far-spreading species

over the wide area of its present distribution; and a long observation of such

will lead to the conclusion that new species must in all cases have arisen out

of variable and widely-disseminated forms. It sometimes happens, as in the

present instance, that we find in one locality a species under a certain form

which is constant to all the individuals concerned; in another exhibiting

numerous varieties; and in a third presenting itself as a constant form quite

distinct from the one we set out with. If we meet with any two of these modifications

living side by side, and maintaining their distinctive characters under such

circumstances, the proof of the natural origination of a species is complete;

it could not be much more so were we able to watch the process step by step. It

might be objected that the difference between our two species is but slight,

and that by classing them as varieties nothing further would be proved by them.

But the differences between them are such as obtain between allied species

generally. Large genera are composed in great part of such species, and it is

interesting to show the great and beautiful diversity within a large genus as

brought about by the working of laws within our comprehension." But to

return to the Zoological wonders of the Upper Amazon, birds, insects, and

butterflies are all spoken of by Mr. Bates in his chapter on the natural

features of the district, and it is evident that none of these classes of

beings escaped the observation of his watchful intelligence. The account of the

foraging ants of the genus Eciton is certainly marvellous, and would, even of

itself, be sufficient to stamp the recorder of their habits as a man of no

ordinary mark. The last chapter of Mr. Bates' work contains the account of his

excursions beyond Ega. Fonteboa, Tunantins--a small semi-Indian settlement, 240

miles up the stream--and San Paulo de Olivenca, some miles higher up, were the

principal places visited, and new acquisitions were gathered at each of these

localities. In the fourth month of Mr. Bates' residence at the last-named

place, a severe attack of ague led to the abandonment of the plans he had

formed of proceeding to the Peruvian towns of Pebas and Moyobamba, and "so

completing the examination of the Natural History of the Amazonian plains up to

the foot of the Andes." This attack, which seemed to be the culmination of

a gradual deterioration of health, caused by eleven years' hard work under the

tropics, induced him to return to Ega, and finally to Para, where he embarked,

on the 2nd June 1859, for England. Naturally enough, Mr. Bates tells us he was

at first a little dismayed at leaving the equator, "where the

well-balanced forces of Nature maintain a land-surface and a climate typical of

mind, and order and beauty," to sail towards the "crepuscular

skies" of the cold north. But he consoles us by adding the remark that

"three years' renewed experience of England" have convinced him

"how incomparably superior is civilised life to the spiritual sterility of

half-savage existence, even if it were passed in the Garden of Eden."

__________________________________

Conteúdo da Primeira Edição - Henry Battes

CONTENTS OF VOL. I

CHAPTER I

.

PARÁ

Arrival— Aspect of the country— the Para Elver— Fu-st walk in the Suburbs of Para— Free Negroes— Birds, Lizards, and Insects

of the Suburbs— Leaf-cutting Ant— Sketch of the climate, his- tory, and present condition of Para 1

CHAPTER II.

PARÁ

The Swampy forests of Para — A Portuguese landed proprietor — Country house at Nazareth— Life of a Naturalist under the equator

— The drier virgin forests — Magoary — Eetired creeks — Abo-rigines 44

CHAPTER III.

PARÁ

Religious holidays— Marmoset Monkeys — Serpents — Insects of the forest —Eelations of the fauna of the Para District . . .86

CHAPTER IV.

THE TOCANTINS AND CAMETA.

Preparations for the journey — The bay of Goajara — Grove of fan leaved palms— The lower Tocantins— Sketch of the river— Vista

alegi-e — Baiao — Eapids— Boat journey to the Guariba falls — Native life on the Tocantins— Second journey to Cameta . . 112

CHAPTER V.

CARIPI AND THE BAY OF MARAJÓ.

"River Para and Bay of Marajó— Journey to Caripi — Negro observance of Christmas — A German Family — Bats — Ant-eaters —

Humming-birds — Excursion to the Murucupi — Domestic Life of the Inhabitants — Hunting Excursion with Indians — Natural

History of the Paca and Cutia — Insects , . . . .168

CHAPTER VI.

THE LOWER AMAZONS-PARA TO OBYDOS.

Modes of travelling on the Amazons — Historical Sketch of the early explorations of the River — Preparations for Voyage— Life

on board a large Trading- vessel — The narrow Channels joining the Para to the Amazons — First Sight of the great River — Gurupa —

The Great Shoal — Flat-topped Mountains — Contraction of the River Yalley — Santarem — Obydos — Natural History of Obydos —

Origin of Species by Segregation of Local Varieties . . .212

CHAPTER VII.

THE LOWER AMAZONS— OBYDOS TO MANAOS, OR THE BARRA OF THE RIO NEGRO.

Departure from Obydos — River banks and by-channels— Cacao planters — Daily life on board our vessel — Great Storm— Sand-

island and its birds — Hill of Pareutins — Negro trader and Manilas Indians — Villa Nova, its inhabitants, climate, forest,

and animal productions — Cararaucu — A rustic festival — Lake of Cararaucu — Moti'ica flies — Serpa — Christmas holidays — River

Madeira — A mameluco farmer — Mura Indians — Rio Negro — Description of Barra — Descent to Para — Yellow fever . . 266

CONTENTS OF VOL. II.CHAPTER I. SANTAKEM. Situation of Santarem — Manners and customs of the inhabitants — Trade — Climate — Leprosy — Historical sketch — Grassy campos and woods — Excursions to Mapiri, Mahica, and Irura, with sketches of their Natural History ; Palms, wild fruit-trees, Mining Wasps, Mason Wasps, Bees, Sloths, and Marmoset Monkeys — Natural History of Termites or White Ants . . 1CHAPTER II.VOYAGE UP THE TAPAJOS. Preparations for voyage — First day's sail — Mode of arranging money-matters and remittance of collections in the interior — Loss of boat — Altar do Chad — Excursion in forest — Valuable timber — Modes of obtaining fish — Difficulties with crew — Arrival at Aveyros — Excursions in the neighbourhood — White Cebus and habits and dispositions of Cebi Monkeys — Tame Parrot — Missionary settlement — Enter the Kiver Cupari — Adventure with Anaconda — Smoke-dried Monkey — Boa-constrictor — Village of Mundurucu Indians, and incursion of a wild tribe — Falls of the Cupari — Hyacinthine Macaw — Re-emerge into the broad Tapajos — Descent of river to Santarem . . . . .71

|

| Adicionar legenda |

CHAPTER III.THE UPPER AMAZONS— VOYAGE TO EGA.Departure from Barra — First day and night on the Upper Amaazons — Desolate appearance of river in the flood season — Cucama Indians — Mental condition of Indians — Squalls — Manatee — Forest — Floating pumice-stones from the Andes — Falling banks — Ega and its inhabitants — Daily life of a Naturalist at Ega — Customs, trade, &c. — The four seasons of the Upper Amazons . 153CHAPTER IV.EXCURSIONS IN THE NEIGHBOURHOOD OF EGA. The river Teffe — Rambles through groves on the beach — Excurion to the house of a Passe chieftain — Character and customs of the Passe* tribe — First excursion to the sand islands of the Solimoens — Habits of great river-turtle — Second excursion — Turtle-fishing in the inland pools — Third excursion — Hunting-rambles with, natives in the forest — Return to Ega . . 225CHAPTER V.ANIMALS OF THE NEIGHBOURHOOD OF EGA.Scarlet-faced Monkeys — Parauacii Monkey — Owl-faced Night-apes — Marmosets — Jupurd, — Comparison of Monkeys of the New "World with those of the Old — Bats — Birds — Cuvier's Toucan — Curl-crested Toucan — Insects — Pendulous Cocoons — Foraging Ants— Blind Ants 305CHAPTER VI.EXCURSIONS BEYOND EGA. Steamboat travelling on the Amazons — Passengers — Tunantins — Caishana Indians — The Jutahi — Indian tribes on the Jutahi and the Junia — The Sapo — Maraud Indians — Fonte Boa — Journey to St. Paulo — Tucuna Indians — Illness— Descent to Para — Changes at Para — Departure for England 367